States from Tennessee to Wyoming have passed laws aimed at ensuring that all students can read. The laws require a variety of specific actions from using instructional methods based on the science of reading to mandating that districts provide teachers with scientifically based professional development. But will these laws work—and how will districts know they are on the right track?

The initial answer is that districts will know they are doing well if children learn to read. It is easy to know if a child can read, and most of us remember those first picture books that we could read all on our own.

I remember Peter in his red snow suit and the tracks he made on the pillowy landscape of The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats. It didn’t snow very much in my hometown of Little Rock, Arkansas, but when at last it did, I was ready.

Few of us remember exactly how we learned to read. Perhaps it was too long ago, or our minds are so transformed by the act of reading that we can no longer remember what it was like before we knew how. Fortunately, teachers can draw on decades of research about how children learn to read.

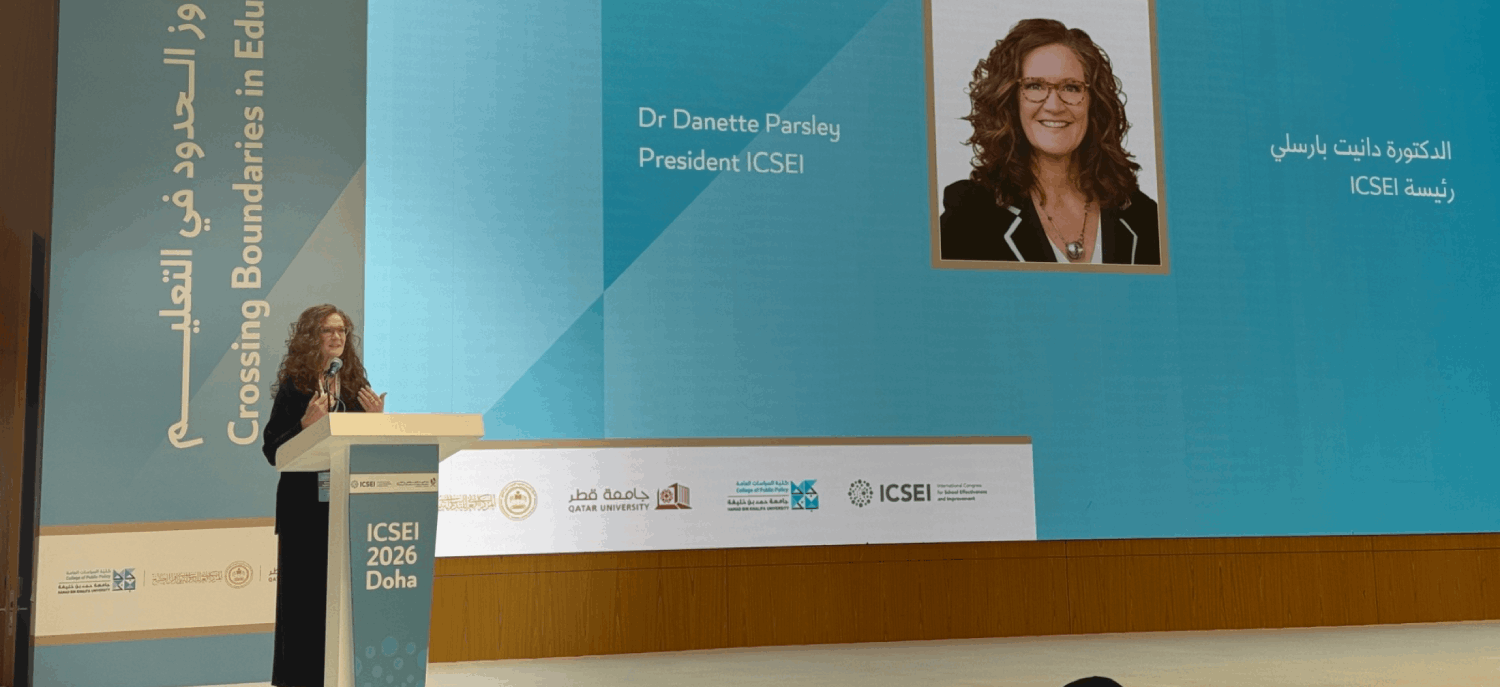

However, teachers cannot do this work alone, and certainly not for all school children, all the time. Based on my experience over the past decade visiting reading classrooms, I believe it takes a powerful districtwide literacy system to ensure that all students learn to read and will read well enough to learn across all content areas.

Students need access to grade-level reading, as well as differentiated instruction that targets the unique reading skills they need to work on. In a class of 20 or 25 students, this means multiple groups and multiple lesson plans, and lots of great reading material.

At Marzano Research, we work with districts to conduct a literacy system review that includes: a review of literacy policies and procedures, a survey of district staff, focus groups, interviews, classroom observations, and an analysis of publicly available literacy assessment data.

We analyze all these data to create a district literacy system profile that identifies areas of strength and potential innovation. We provide recommendations for ensuring literacy practices, supports, and assessment systems are grounded in research and evidence-based practices and that systems are designed to meet the needs of all learners. Our team then brings staff together to understand and make sense of the data so they can take action to strengthen literacy instruction in their district.

We see this review as part of an ongoing improvement process that is fundamental to initiating and sustaining positive change. Our team both builds on the district’s existing strengths and identifies opportunities for adding new evidence-based literacy practices.

Our approach is grounded in the evidence base that defines the critical knowledge and skills for literacy development, as well as research on best practices for teaching. Some of the sources we draw upon include the Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read and What Works Clearinghouse Practice Guides that address literacy topics.

I know that the really important work of building a system of supports for reading instruction happens after the literacy system review, and I’ve been heartened by practitioners’ responses to it. One district leader shared: “Just wanted to follow up and thank you for the wonderful session today. Comments from the team included:

- ‘I couldn’t believe how quickly the four hours passed!’

- ‘This was a great discussion.’

- ‘This helped solidify what we knew was needed, but highlighted areas that we may not have focused on initially.’

- ‘Backing up our rationale with data will be huge as we write our goals.’

Most importantly, I want to thank you for emphasizing that I am not alone in this process; I have a great team of experts behind me!”

As these comments imply, ensuring that all children learn to read is not as easy as simply testing children to identify those who are and aren’t literate. Instead, districts need to examine the district systems that support literacy instruction. Then, they need to take actions that improve the system. By examining multiple data sources about district literacy systems and by harnessing collaborative effort throughout the district, more students are likely to learn to read well.

If you would like to learn more about how we can partner with you to create a road map to guide your literacy efforts, please reach out to me here.